Diversity Champion: Dr. Nakia Parker

August 19, 2021 - Liz Schondelmayer

Dr. Nakia Parker is an MSU Assistant Professor of History and past College of Social Science Dean’s Research Associate with expertise in African American history. Since arriving on campus in 2019, she has established herself as an expert on topics such as slavery, reconstruction and the early fight for civil rights.

Dr. Nakia Parker is an MSU Assistant Professor of History and past College of Social Science Dean’s Research Associate with expertise in African American history. Since arriving on campus in 2019, she has established herself as an expert on topics such as slavery, reconstruction and the early fight for civil rights.

After earning her PhD from the University of Texas at Austin in May of 2019, Dr. Parker relocated to East Lansing and immediately got to work, presenting her research at MSU's inaugural Juneteenth celebration. Her passion for her work is driven by her love for history and the importance of portraying the past accurately.

I first became interested in these topics at a young age, after noticing the differences between the histories I learned and was taught to respect at home versus what I learned in school about these three topics. Learning about slavery and African American history at school was relegated to a few prominent personages, like Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King, and primarily emphasized during Black History Month in February. American Indian history was marginalized even more. Yet, our library at home had an abundance of history books and documentaries about all of these subjects! I also remember the times my mother or father corrected information shared by teachers or museum tour guides about slavery and the lives of Black and Native people on school field trips that they attended with me despite not being trained formally as history teachers.

My interest in the intersection of these three subjects occurred when I was an undergraduate majoring in history at the State University of New York at New Paltz. I took a class on the American Civil War and went to office hours to discuss ideas for my final paper with my professor. I decided I wanted to write about American Indian participation in the Civil War. And I was shocked when he told me that some Native American nations, like the Cherokee, participated in the enslavement of people of African descent and served in the Confederate Army. This was not what I expected to hear and certainly not what I learned at home or at school.

Eventually, with the support of professors in the History and Black Studies departments at New Paltz, I decided to pursue a graduate degree in history and went to UT Austin to work with Daina Ramey Berry, one of the top scholars in the field of slavery studies, African American history, and African American women’s history (and a former MSU professor). So the moral of this story for students is go to office hours! You never know what one brief conversation with a professor will mean for your future.

While Dr. Parker is committed to conducting academic research, she also believes in sharing what she learns with others - including future educators and historians.

My current academic project is revising my dissertation, Trails of Tears and Freedom: Black Life in Indian Slave Country, 1820-1866, into a book manuscript. It examines the forced migrations, labor practices, family life and kinship networks, and resistance strategies of people of African and Afro-Native descent in Choctaw and Chickasaw slaveholding communities from the period of Native American removal in the 1830s to the abolition of slavery in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations in 1866. It will be the second full-length historical monograph on chattel slavery in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. Earlier this year, The Journal of African American History published an article based on chapter five of my dissertation that discusses family life and community.

Some of my favorite projects, however, have been in the realm of public history. While a graduate student, I helped craft the text for the Texas African American History Memorial on the Capitol grounds in Austin. I’ve written and done podcasts that discuss learning about and teaching slavery, African American, and American Indian history that were geared toward students, elementary and secondary school history teachers, and the general public. Providing appropriate language and helpful pedagogical methods for teaching topics like slavery and Native American removal is important to me, especially when I think about my own experience in school and the scant information I’ve received about these important histories.

I’ve had many students in the classes I’ve taught so far at MSU that plan to be future history teachers, and I’m encouraged to see how many of them have seriously thought about how they can engage their own students on how to grapple with these “hard histories.” I’ve learned a lot from these future educators!

When it comes to most people's understanding of the Atlantic slave trade, there are several gaps that Dr. Parker bridges with her expertise. Below, she identifies common myths or misunderstandings and provides clarification.

One of the most common myths that I hear about the slave trade is “Africans sold their own people into slavery.” This statement implies that Africa is one country and that Africans are a homogenous group of people. But in fact Africa is a diverse place, and during the time of the

international slave trade, different groups and nations engaged in conflicts with one another for supremacy. Participation in the slave trade becomes a means to get rid of enemies, obtain goods, etc. We usually don’t say, “Europeans did this or that” we say, The English, the French, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the Dutch. We can think of early African societies in a similar manner. For example, Ghana, Mali, and Songhay were powerful empires that traded with foreign countries, had complex social and religious structures, and created institutions of higher learning. Like European nations, each of these empires had their own specific political, economic, and social interests.

One thing I would like Americans to learn about the trade in school is that most captives in the slave trade did not come to what we now know as the thirteen British colonies in the United States. In fact, only 4 percent, or approximately 400,000 people out of over 12 million came to the U.S. Most African captives during the time of the slave trade went to Brazil (almost 5 million). But the United States is the only country that had a self-reproducing enslaved labor force. By 1860, there were 4 million enslaved people in the United States worth billions of dollars. It was the dominant slave-holding nation in the Western Hemisphere.

Finally, Dr. Parker shares ways that each of us can treat victims of the slave trade with the dignity and the respect that they deserve.

There has been a lot of discussion among historians about the use of language, and I think that’s an excellent way to talk about this topic respectfully and accord victims of the slave trade with dignity and respect. For example, using enslaved person instead of slave, enslaver instead of slave owner or master to emphasize what was done to captives and who did the enslaving.

Having open and frank discussions in school and public about the history of the slave trade and abolition instead of minimizing it or taking it out of schools altogether is necessary. MSU has an excellent website, enslaved.org, for academics and members of the public to learn about the personal histories of people involved in the slave trade. And no conversations, learning, or reconciliation attempts about the slave trade or slavery in general are complete if we don’t include the issue of reparations for descendants.

Read more:

Diversity Spotlight

Alumni

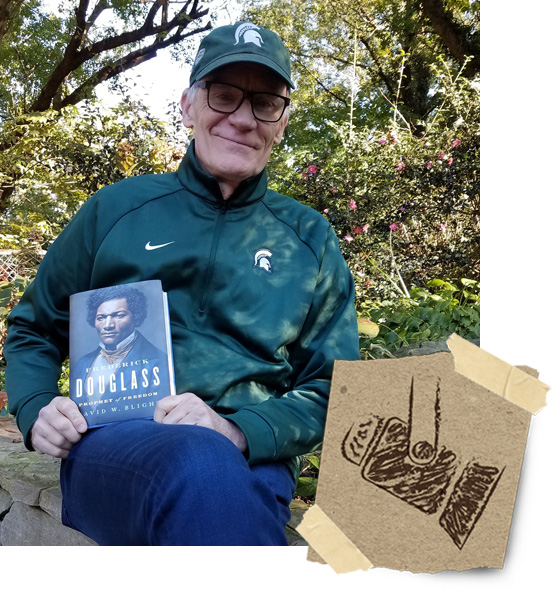

Dr. David Blight

Dr. David Blight, an MSU History Alumnus, is a Sterling Professor of History, African American Studies, and of American Studies at Yale University. Dr. Blight is also the Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition.

Diversity Torch

Student

Zach Sneathen

Mr. Zach Sneathen is a fourth-year MSU undergraduate majoring in Interdisciplinary Studies in Social Science, who took an African American History class with one of the college's newest assistant professors, Nakia Parker, in which he produced a podcast that discusses the importance of using appropriate language when talking about the history of slavery.

Diversity Matters

We strive to cultivate an inclusive and welcoming college environment that celebrates a diversity of people, ideas, and perspectives.