Deconstructing the system of mass incarceration

October 18, 2021 - Katie Nicpon

Emilie Smith, PhD, professor and MSU Youth Equity Project lead in the MSU Department of Human Development and Family Studies in the College of Social Science, welcomes participants to the Sept. 17 panel Pipelines to Mass Incarceration: Policing, Sentencing and the Incarcerated. Right to Left: Emilie Smith, Derrick Jackson, Anna Gersh, Matt Tjapkes, Carol Siemon and Gregory Pittman (full titles included in the story). Photo credit: Aaron Word, MSU Broad Museum.

“I am what injustice looks like,” said Kenneth Nixon. He was exonerated in February 2021 after serving 16 years for a crime he did not commit, and now serves as the chairman of the National Organization of Exonerees.

“There’s been a lot of talk about change,” he continued. “But that has been talked about by people who have not been directly affected by that change. All the change that’s happening on the back side of this is being made by people that don’t have to experience what it looks like on the other side. People that have spent their careers in suits and in offices don’t know what the inside of a prison cell or a police car looks like. There’s a lot of progress being made, but there is a lot more to do. And that progress can’t be made without the voices of the people that this is affecting.”

Nixon attended a panel hosted on September 17, 2021, by the MSU Youth Equity Project and the MSU Broad Art Museum. The panel was made up of Michigan community and justice-system leaders to discuss more effective approaches to public safety, equity, and justice.

According to the ACLU, 2.3 million individuals are incarcerated in the United States, representing 25% of people who are incarcerated in the world. Mass incarceration is affected by police, legal, sentencing, and corrections practices and policies. Each of the members of the panel represented these intersections of the justice system: Judge Gregory Pittman from Muskegon Family Court; Carol Siemon, Ingham County prosecutor; Derrick Jackson, Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office director of community engagement; Matt Tjapkes, director of Humanity for Prisoners; and Anna Gersh, PhD, director of One Love Symposium. The panel discussed their efforts to dismantle the system from within and also important calls-to-action for community members. The video of the panel is available to watch online.

“People make assumptions that criminal justice and social work are opposite ends of the spectrum, but they’re not, and I get to live in that intersection of the two,” said Derrick Jackson, director of community engagement at the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office. During his early career as a social worker, Jackson gave examples of working with Washtenaw County youth and witnessing police officers as the first connection to people who needed access to resources such as homeless shelters or centers for survivors of domestic violence.

Derrick Jackson, director of community engagement, Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office, (middle), describes the intersection of criminal justice and social work. Photo credit: Jacqueline Hawthorne, College of Social Science.

In addition to building a police force with a service and social work mindset, Jackson also spoke about the importance of communities working together to create public safety through treating the root causes of crime and incarceration.

“What services do we need to provide that can help people with mental health, addiction and homelessness?” he gave as examples.

Ingham County Prosecutor Carol Siemon represented the trial and prosecution phase of mass incarceration, and shared some of her efforts to make change within the system.

“I’ve enacted two policies recently, one is traffic stops saying that for non-public-safety traffic stops, such as tinted windows, dangling ornaments and broken taillights and all those non-public-safety traffic stops that have disproportionately led to arrests, injuries, deaths and really tragic outcomes, we’re not going to do them any more.”

Additionally, Michigan has an add-on policy called Felony Firearm, which means that if a person is convicted of a felony where a gun was present but not used, they get an automatic two years in prison added to their sentence.

“Safe and Just Michigan just released a report that showed that statewide, 80% of the people serving time under Felony Firearm are Black,” she said. “And this was true for my county too. So what I said was that we can charge underlying offenses, but we need to pull off the crimes that are linked to the racial disproportionality in prison.”

Judge Gregory Pittman from Muskegon Family Court addressed his sphere of influence as a judge.

“We have to be social workers, because we have to be concerned about the human condition from the bench,” Pittman said.

He named pretrial incarceration as an important area for the public to scrutinize.

“We have to look at how we deal with people released on bond before they have to come back to court. We can shape it or say it anyway we want, but that person is incarcerated until they can get a date in court, enter a plea, or find a way to find the money to post bail,” he said.

Additionally, Pittman advised community members to ask their local judges who served on the School to Prison Pipeline project in Michigan that established a partnership with schools to reduce youth incarceration rates and bring together mental health and other service agencies to provide better support for young people across Michigan.

“Michigan has incredibly high numbers and the most punitive measures for juveniles,” Siemon added. “We have no juveniles serving lifetime parole in Ingham County, but we still have over 200 in the state.”

Once a person enters prison, they are identified by the number that represents their crime.

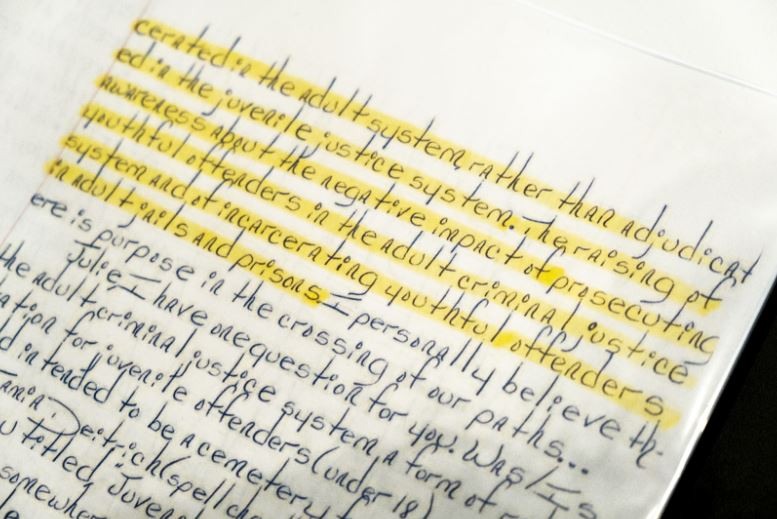

Youth who are incarcerated wrote letters about their experiences in the justice system and its effect on their lives. This letter is on display at the MSU Broad Art Museum as part of the exhibit focusing on mass incarceration. Photo credit: Jacqueline Hawthorne, MSU College of Social Science.

“Because every person is given a reminder of their mistakes, we wanted to remind them that they are worthy, they are someone’s child, they are a human being,” said Matt Tjapkes, director of Humanity for Prisoners.

The purpose of Humanity for Prisoners is to provide, promote and ensure—with strategic partnerships— personalized, problem-solving services for incarcerated people in order to alleviate suffering beyond the administration of their sentences. Tjapkes described helping prisoners navigate the parole system, answering their questions, sending them photos, and just reminding them that they matter.

“Kindness is in short supply in prison, and we hope to provide a little bit every day,” he said.

Additionally, along their pathway through incarceration, a person will encounter multiple people who work within the criminal justice system. Anna Gersh, PhD, director of the One Love Symposium, is using her research to create training for all of the criminal justice workers that will emphasize empathy, service, and other universal human values, and how to apply that to their service interactions.

"There is a gap in the literature around what happens at the point-of-service moment. That moment where a service professional is making a decision about you. The One Love Symposium is engaging a diverse group of non-professional community members to help us develop a better understanding of this moment. We believe this will help many service professions, including but not limited to those in the criminal justice system, to improve their decision-making practices and better serve individuals whose livelihoods may be dependent on those decisions."

Another part of the broken system of mass incarceration are the experiences of people who leave the justice system after serving their time, only to have to continue to serve a different type of sentence in society for the rest of their lives. According to the ACLU, 650,000 men and women nationwide return from prison to their communities each year, but they face nearly 50,000 federal, state, and local legal restrictions that make it difficult to reintegrate back into society.

Jackson views local and state government as the first places that need to have representation from people who have lived experience of our justice system.

“Who better to engage with, help, to lead, than folks who have lived that experience, understand what that life is and how the system really works,” he said. “They speak the language, have the trust, and have the authority to shift communities and shift neighborhoods. We hire more people with lived experience than any other government department.”

The panel included a time for participants to share their stories, comments or ask questions.

“To understand our justice system, we have to understand the antecedent of the thing,” said Edward Sanders who goes by Barakah, which means “blessings of God.”

“The supreme law in this country is the Constitution, and we have to look at the 13th Amendment,” he said.

Barakah, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan School of Social Work, working in the Conviction, Integrity and Expungement Unit for Washtenaw County, was sentenced to life without parole when he was 17 years old and served 43 years of his sentence.

“The top part is about freedom, but the second part is the exception. Except for those who are lawfully convicted and sentenced,” he said. “And we fought a civil war only to get that exception.”

Even though the 13th amendment offered freedom, the exception for people incarcerated ushered in a new form of enslavement. He called on the panelists and attendees to critically analyze the exception as the root cause of the issues with our justice system today.

“In addition to going back to your communities and talking with people of power, I think it’s equally as important to get to know people who have gone through the criminal justice system,” said Victoria Burton-Harris, Chief Assistant Prosecutor in Washtenaw County and event participant. “Get to know these people: that creates and expands your capacity for empathy. Until you live, work and play with people who have lived in these cages, you cannot begin to understand and advocate. And if you don’t understand, it’s harder to have empathy. And if you don’t have that empathy, you miss opportunities to help share their stories.”

The panel was hosted as a collaboration between the MSU Youth Equity Project and the MSU Broad Art Museum. The mission of the MSU Youth Equity Project is to reduce disparities and advance health, justice, and wellbeing among marginalized youth and families through community-engaged, interdisciplinary research. Emilie Smith, PhD, is a professor and the MSU Youth Equity Project lead from the MSU Department of Human Development and Family Studies in the College of Social Science. She was grateful for the chance to host such a meaningful community conversation and hopes that more Michiganders will join in the upcoming conversations around youth justice on Oct. 29, and Nov. 12, at the MSU Broad.

“We hope that people from every sector of the community will join us for these important conversations around supporting youth and their development as they navigate these systems and also how to empower them to express themselves creatively,” she said. “These conversations are important because we all have an important role to play in changing our society.”

To learn more about upcoming MSU Youth Equity events, visit: https://bit.ly/3vpi6jr