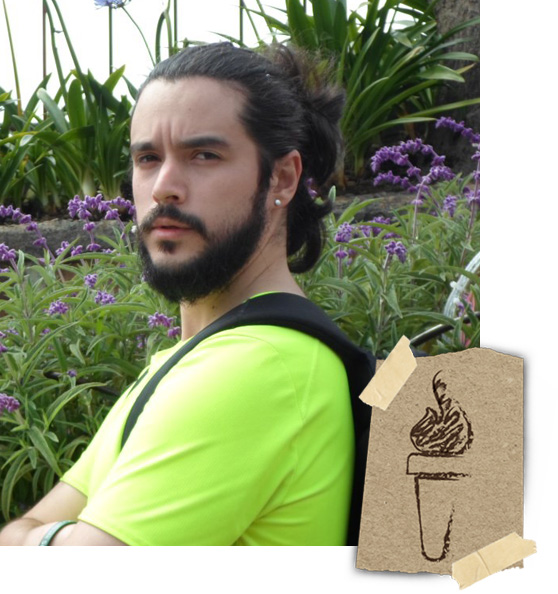

Diversity Torch: Mr. Juan Carlos Rico Noguera

November 30, 2020 - Liz Schondelmayer and Brandon Drain

Juan Rico Noguera is a PhD student within the Department of Anthropology at the Michigan State University College of Social Science. Born in Colombia, Juan's research focuses on the Colombia Truth Commission (CTC), which gathers information and data to shine a light on human rights violations committed during the nation's violent past.

Juan Rico Noguera is a PhD student within the Department of Anthropology at the Michigan State University College of Social Science. Born in Colombia, Juan's research focuses on the Colombia Truth Commission (CTC), which gathers information and data to shine a light on human rights violations committed during the nation's violent past.

Juan earned his undergraduate degree in Political Science and a Master's degree in Cultural Studies in Colombia before traveling to the U.S. for his PhD. Along the way, he developed an interest in researching the CTC.

As an undergraduate, I studied Political Science in the Sergio Arboleda University. When I was pursuing that degree, I really enjoyed political theory but not the empirical engagement with official institutions, so I switched to Cultural Studies for my Master's degree. In the Master of Cultural Studies program, I started to concentrate on the relationship between the production of knowledge and particular distributions of power in society.

I started researching the production of memory in Colombia regarding human rights violations in the past and the present. Colombia as a country has been suffering from armed conflict for more than 60 years now, with a very complex relationship with violence. The state and other actors have been systematically violating the human rights of millions of people. I was trying to understand how knowledge about those human rights violations was produced and distributed through society, because there are various accounts of whether those violations actually took place, and to what extent. Because I was interested in this issue, I looked for a PhD program to carry on my research. I came to MSU after discovering the work of Dr. Elizabeth Drexler.

Juan explains more about the mission of the CTC, and his research pertaining to it.

Truth commissions are institutions that seek closure for traumatic events of the past, and seek to make visible human rights violations that not everyone knows about. The idea is that, through the knowledge of those facts, we can build a different society—a society that isn't going to repeat those massive human rights violations.

A research topic I'm exploring, for example, is how narratives about the past are built by particular bodies of expertise. For example, other narratives that are being produced by various institutions, organizations, and social movements, sometimes conflict with the narrative of the CTC. I am interested in the way in which the CTC commissioners build these narratives, and how those narratives survive and engage with narratives that are coming from different bodies of expertise.The very idea of who is an expert on the Colombian violence and what makes them experts is also a part of my research.

Until now, I have been able to travel to Colombia a couple of times to interview people working in the CTC, as well as people working outside of it. All of them are trying to build a representation of the past in different ways. People close to the armed forces, for example, are very critical about the Truth Commission, saying it is biased. In that way, they are basically inviting the public to distrust what institutions like the CTC are trying to depict. I have also been able to talk with groups of victims that have formed social movements and are backing up the CTC. As you can see, there are a lot of accounts at play here, and I'm trying to better understand this messy relationship Colombians have with their past.

Juan explains how human rights can be understood as a language.

There are different ways in which we can understand human rights. The most dominant definition is that they are the rights we all have by nature.

As an anthropologist, however, I understand human rights as a language. It is a way in which we describe the universe, create an identity, and talk about the human experience. For example, in Colombia, it is difficult to find references to "human rights" before the 1980s. Then, the people that started to talk about human rights using this particular language were leftists, belonging to political groups that were harassed by the state. Over time, even the armed forces have had to engage with human rights language to establish a meaningful and productive relationship with the courts and with the public. Every military action today has to prove it is respectful of human rights.

Finally, Juan opens up about the struggle to get people to take action when human rights violations occur - and what needs to change for us to tackle these issues around the world.

The human rights movement across the world has used a lot of strategies to intervene when violations happen. For example, one of those strategies is to increase visibility of the issue, by taking pictures, taking videos, and reporting on what's happening. This comes from the idea that human rights violations can only happen under a veil of mystery and invisibility. And I think that makes a lot of sense.

Sometimes, however, this visibility does not have the intended consequences. For example, in Colombia, every day we see on the news that human rights defenders are being killed. It's happening right in front of our faces - everyone knows it's happening, and yet, nothing happens. Bringing these horrible actions to light isn't having the effect it had in the 1990s. I think we need to try to imagine different ways to get people involved.

People are no longer feeling these things, maybe because we are becoming over-exposed to the violence. We just start to think that it's normal. There is very interesting literature on how professional human rights defenders burn out. They get tired of seeing the atrocities time and time again, and they start to feel that they don't have any power to make a difference. That has happened with professional human rights defenders. Now that all of us have access to this information and images, I think we as a society may be burning out. It's a really difficult spot we are living in, in terms of protecting human rights.

Read more:

Diversity Champion

Faculty/Staff

Dr. Monir Moniruzzaman

Dr. Monir Moniruzzaman is an associate professor in the MSU Department of Anthropology. His research examines human organ trafficking within the black market, and how to combat this human rights violation.

Diversity Spotlight

Alumni

Karen Phillippi

Karen Phillippi, a MSU Anthropology alumna, celebrates a career in immigration law and is now the Director of New American Integration with the Office of Global Michigan.

Diversity Matters

We strive to cultivate an inclusive and welcoming college environment that celebrates a diversity of people, ideas, and perspectives.