Diversity Champion: Dr. Monir Moniruzzaman

November 30, 2020

Dr. Monir Moniruzzaman is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at the Michigan State University College of Social Science. His research examines human organ trafficking within the black market, and how to combat this human rights violation. Community-Academic Innovation and Dissemination (Community-AID) lab, which studies ways to support the success and well-being of families and youth of all backgrounds.

Dr. Monir Moniruzzaman is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at the Michigan State University College of Social Science. His research examines human organ trafficking within the black market, and how to combat this human rights violation. Community-Academic Innovation and Dissemination (Community-AID) lab, which studies ways to support the success and well-being of families and youth of all backgrounds.

Dr. Moniruzzaman's lifelong goal was to be an anthropologist. As a master's student, however, he discovered his life's purpose: combating illegal organ trafficking.

I completed my PhD from the University of Toronto and joined MSU as an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology in 2010.

It was a lifelong goal of mine to become an anthropologist. My bachelor's and master's degrees are also in Anthropology. When I was a master's student, I read an article about the global market of human organ trafficking, which is the buying and selling of human body parts on the black market. Before I read that article, I had never thought that such kind of dehumanization and exploitation could happen in human history. I couldn't believe it.

So, I decided to do my PhD in medical anthropology, and write my dissertation on human organ trafficking. I've been doing this work for nearly two decades, and I've established myself as one of the experts in this field.

While human organ trafficking is a complex phenomenon, Dr. Moniruzzaman's research focuses predominantly on the seller's perspective.

As a PhD student, I went to Bangladesh and conducted yearlong ethnographic fieldwork to investigate the illicit trade in human organs, including kidneys, livers, and corneas. Before doing my fieldwork, I found that a handful of research came out about the recipients of these organs, most of whom lived in the West. But I wanted to look at the other side of the story - people who are selling their body parts. Who they are, what is the process of selling an organ, and how they are living in their damaged bodies. I was drawn into that.

The field work was extremely challenging. For the first four months, I couldn't find anyone to talk to. No one, not even doctors or recipients involved in the trade, would disclose who sold them the organs. The sellers were extremely hidden.

I tried talking to four organ brokers, which was very risky. I was being followed, and I couldn't go outside after dark. It was a frightening experience. However, with one broker's help, I was able to interview 33 kidney sellers who sold their kidneys in the black market. These are live people, not cadavers. I learned from them what kind of deception, manipulation, coercion, and breach of consent led them to make such a decision.

The brokers basically entrap them, promising them a large amount of money (which they never get in the end), and lure them in with a story about the "sleeping kidney." This is a common lie told by brokers, that one kidney sleeps while the other one works, so in the operating room, the doctor can turn on the sleeping kidney and give the other one to another patient who needs one. The brokers present it as a win-win, no-risk situation, and a noble way to help other people.

Dr. Moniruzzaman has since expanded his research to focus on other parts of the world, and other organs that are being trafficked.

Organ trafficking happens all over the world. There are some hot spots - notably South Asia, the Middle East, and South America - but it's advancing in many countries. It's so hidden that it's hard to get that data to map out the current state of organ trading worldwide.

The kidney was the first organ that doctors started performing, because the human body has two. That's why kidneys became the dominant organ we can see in the black market. Recently, however, I published an article about liver trading, as a lobe of liver can be cut off and be transplanted into another body. For that article, I talked to two liver sellers.

They are both young people, still in their twenties. One didn't know what "liver" meant in English, nor its function in the body. The operation took 20 hours, and he doesn't have enough money to pay off his post-operative care, and his body doesn't allow him to do any physically demanding jobs. So, he's living much worse than before.

I also found that there are cornea sales. I talked to one woman who wanted to sell her cornea, because she says she doesn't need two eyes to see the world. She's a single mother and works as a house maid, so she wants to sell a part of her eye to get by.

After learning more about this problem, Dr. Moniruzzaman isn't just focused on research. He is focused on action.

I believe that Academia is not just for knowledge production: we need to translate our work to enact meaningful changes. For example, I am a member of a task force on organ transplantation at the World Health Organization. We monitor the situation, and try to combat this practice worldwide. I was invited by the Vatican and we crafted a resolution that was signed by Pope Francis and distributed around the world. I also gave a talk to the U.S. Congress Human Rights Commission and US Senate Foreign Relation Committee. It’s challenging to curb such an egregious human rights violation. It's not going to happen overnight, but persistent work can improve the situation.

After World War II, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which stated that all humans on this planet are entitled to certain necessities to live, such as food, water, shelter, et cetera. We have made some progress towards political rights, but if you look at economic rights, we have failed completely. Most people in the world live in poverty and 10% of world populations live on less than $2 a day or in constant hunger. This has some tragic consequences and that led to human organ trafficking around the world.

We cannot live in a world where human bodies are bought and sold on the market place. It's dehumanizing, like slavery. As economic inequality increases at an unprecedented level, including in the United States, we cannot create a world where certain populations need to sell their body parts for their physical survival. The poor have every right to keep their body parts intact. In this context, we must think of human rights as bodily rights as well.

Read more:

Diversity Spotlight

Alumni

Ms. Karen Phillippi

Karen Phillippi, a MSU Anthropology alumna, celebrates a career in immigration law and is now the Director of New American Integration with the Office of Global Michigan.

Diversity Torch

Student

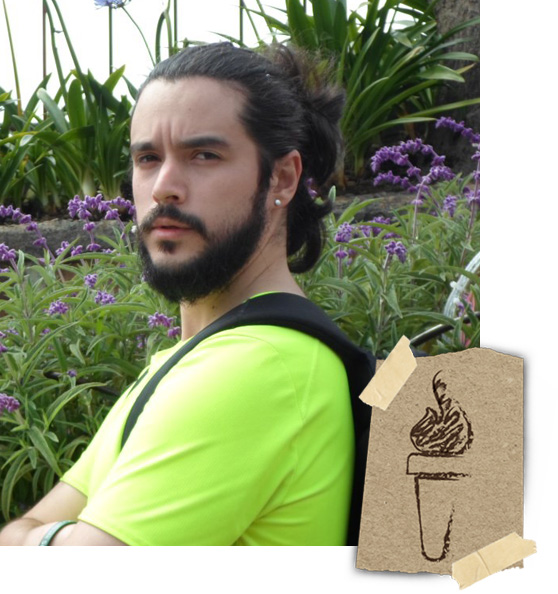

Mr. Juan Carlos Rico Noguera

Juan Rico Noguera is a PhD student within the MSU Department of Anthropology. Born in Colombia, his research focuses on human rights violations committed in the nation's past.

Diversity Matters

We strive to cultivate an inclusive and welcoming college environment that celebrates a diversity of people, ideas, and perspectives.